Biomass burning in East Anglia was seen as a way of maximising use of the region’s supply of softwood timber while kick-starting local forestry from the bottom upwards, bringing local forest and woodland back into management. Biomass burning in Suffolk was seen as the logical route to the reinvigoration of predominantly pine forest plantations across the region, often plagued by Dothistroma needle blight (red band needle blight (RBNB)) a debilitating disease with roots in the 1990s.

Local companies including woodland owners, small forestry contractors, wood processors and energy consumers were all seen to benefit, although sustainability of a locally-focussed biomass burning system would clearly depend on a strong FC-led commitment to maintaining local timber supplies in the longer term. New planting had crashed after the ‘Lawson Budget’ in March 1988 and is yet to recover. Lawson’s short-sighted budget took away tax breaks given to forward-looking landowners to plant timber trees. At the time ‘Lawson’s law’ was hailed as progressive by many outside of forestry but in retrospect is now seen as a disaster for UK commercial forestry.

Rise and fall of biomass burning in Suffolk

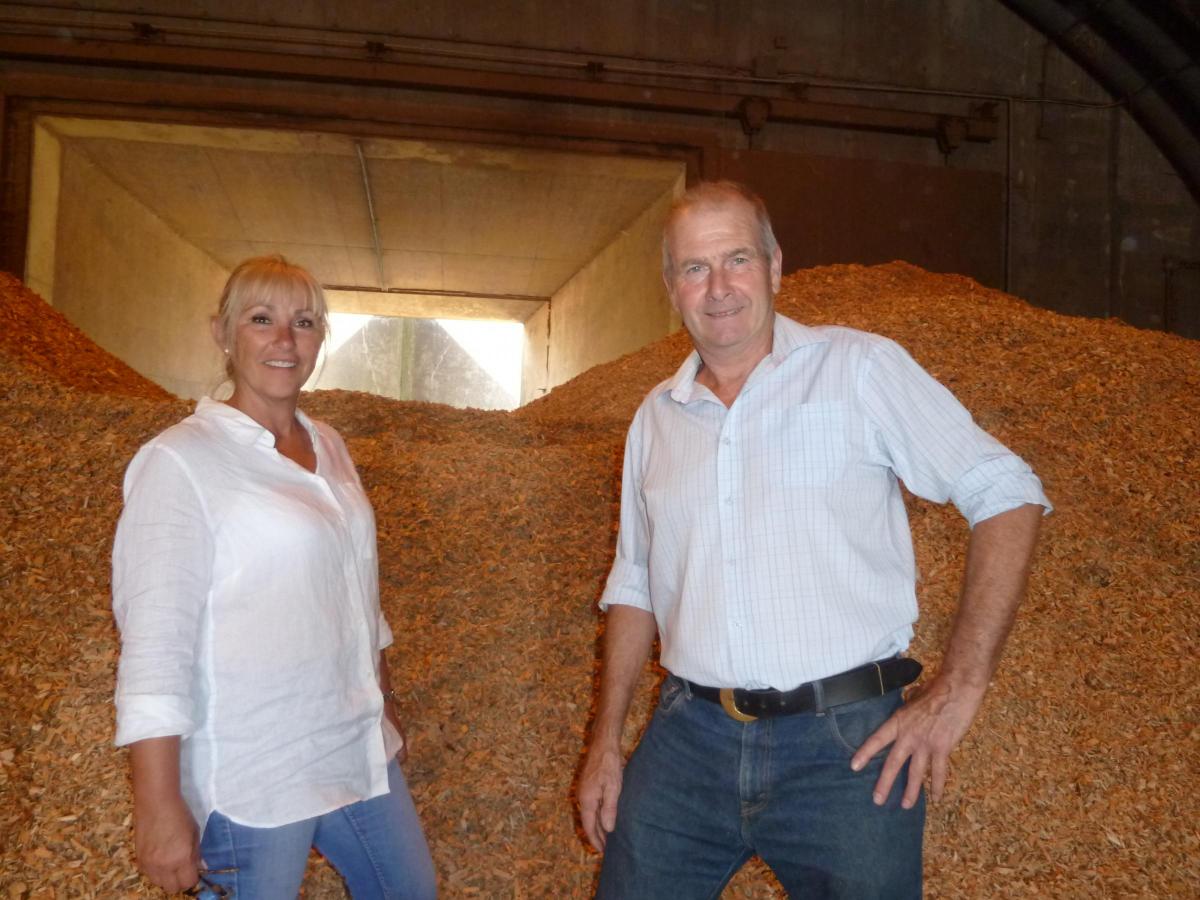

Sarah Brown is Director of Bentwaters Parks in Suffolk, a company which covers a wide range of business activities in agriculture and forestry. Eastern Woodfuel Ltd, part of the Bentwaters Parks group, processes locally-harvested timber resources into woodchip for biomass burning in both commercial and private sectors.

“Forestry is a massive part of the Suffolk scene,” says Sarah Brown. “Forestry and downstream activity like woodchip for biomass here at Eastern Woodfuel have been thriving for years, but is now confronted by dwindling timber reserves, hastened by FC-encouraged trends to convert clearfelled forest land into lowland heath and other open habitats.”

The meeting with Forestry Journal was arranged by Kevin Ross, local forestry contractor and elected member of neighbouring Tunstall Parish Council (‘Keeping the door ajar’, Forestry Journal January 2018) who backed Sarah’s assertions. “

“After the Great Storm in October 1987 this whole area was replanted with commercial softwood species but compartments now less than 30 years old are being handed out in Farm Business Tenancies even before the first thinning. And not even waiting to harvest full term trees, so anxious it seems is FC to deforest the area,” Sarah and Kevin told Forestry Journal.

“I fail to see the sense or logic behind such moves,” says Sarah. “Tall evergreen conifers reduce wind erosion of light sandy soils by strong onshore easterly winds felt in this part of Suffolk. They buffer against extreme cold in winter while research shows both therapeutic and educational benefits of well-wooded environments and their superiority over those without trees.

“We have tended to take our forests for granted but are visibly losing this valuable resource bit by bit before our very eyes. I would like to think the astronomically high price (and rising) for timber might concentrate and change minds about planting conifers, but whatever happens we are fast approaching a 30-year hiatus in softwood supplies. It might not be so bad if we ended up with a patchwork or mosaic but this is solid – continual and continuous deforestation across the landscape, with no restocking let alone new planting as the single-minded goal,” said Sarah.

“Suffolk has an unrivalled range of environments and variety of habits,” said Kevin, citing coniferous forest plantations, semi-natural broadleaf woodland, lowland heath, wetland and salt marshes. “Why narrow this down with such a short-sighted policy?” he asks.

Biomass burning gets off the ground

Sarah Brown produced the document which kick-started biomass burning in East Anglia, called Woodland for Life’ – The Regional Woodland strategy for the East of England, published by the East of England Regional Assembly and Forestry Commission in 2003.

Sarah says Eastern Woodfuel was set up following a meeting with Gary Battell, Woodland Advisory Officer for Suffolk County Council, who were then thinking about replacing oil-fired boilers in its schools with biomass boilers. Back then the incentive for change came in the form of a ‘Bioenergy Infrastructure Grant’ (BIG), created, operated and awarded by Defra. In essence, the idea was to process wood into chips and pellets to encourage companies and private individuals to try alternatives to fossil fuels. At the time Defra was offering a more than generous and appropriately named BIG as 30% of the cost for purchase and installation of biomass boilers.

Interested parties applied for a BIG and duly received a lump sum after installation. It was a ‘one-off’ payment unlike the current RHI which pays according to how much is burned – ‘the more you burn the more you earn’. However, even with a substantial 30% grant, biomass boilers were still a whole lot more expensive to install than oil-fired boilers. However, the benefit was seen in its environment-friendly credentials.

Inspiration for the system came from Scandinavia where most of the hardware originated, and where energy requirements for whole villages were provided by biomass boilers. “Suffolk County Council came to us because of our strategic location between Rendlesham Forest and Tunstall Forest,” says Sarah. “The idea was to use ‘bent’ timber which is not a waste product but a by-product of forest harvesting.”

At that time this grade of timber was transported all the way to Kronospan in North Wales at the cost of £400 per lorry load, with a small amount going to Bedmax to produce wood shavings for animal bedding. High contemporary demand for timber for processing into equine bedding is a key reason why Eastern Woodfuel is now approaching an acute wood supply problem.

A common sense system

In both concept and reality biomass burning made supreme sense at the local level in Suffolk. Fantastic for local companies now presented with the opportunity to buy locally-grown timber and make money selling the finished end product. And good for East Anglia’s small forestry contractors who could make full use of local forest resources and sell directly to the processor.

“In those days FC was ‘banging-on’ about ‘wood miles’ which would clearly be reduced by novel moves to maximise local use of East Anglian-grown timber,“ said Sarah. “Rarely can you say that something is ‘win-win’ all round but biomass burning was just that. All the right boxes were ticked – locally-grown standing timber cut by small local forestry contractors with opportunities for new locally-based wood processors to sell finished products to keep the home fires burning.”

Eastern Woodfuel was established some 10 years ago using local supplies of Corsican and Scots pine. “Not only do we need a consistent supply of timber but also species stability to satisfy the physical specifications for wood-chipping and chemical specifications related to calorific value of the finished product. Ten years on we still use only Corsican and Scots pine to ‘square a good green circle’ right on the doorstep,” says Sarah.

RHI takes over

RHI was introduced in November 2011 using a completely different incentive – ‘the more you burn the more you earn’. “It was not without problems,” says Sarah. “Clients who had received the 30% BIG grant could not apply for RHI, which meant the innovators who made the switch early, got biomass burning off of the ground and showed others the way, were unfairly penalised.”

There were all sorts of regulations together with yawning gaps, not always logical. “RHI only allowed use of virgin wood which prevented us from using mountains of readily-available recyclable wood including pallets and potato boxes,” says Sarah. Timber supply went from the sublime to the ridiculous, with sawlog-quality timber ending up in biomass burners and power stations and not at the region’s sawmills where it should have been. This remains a not uncommon occurrence which Sarah describes as ‘scandalous and bordering on sacrilegious’. Indeed Forestry Journal has seen for itself stacks of sawlog-specification timber including Douglas fir, larch and Scots pine all destined for the biomass boiler (Bridging the gap – Forestry meets arb in Suffolk, Forestry journal August 2015).

There was always a deep-seated problem around longer term supplies of locally-produced wood resources for biomass burning in East Anglia, now showing up in the escalating cost of timber, irrespective of type and grade. “In the early days our timber supply was more than adequate and near at hand,” says Sarah, adding how Eastern Woodfuel was regularly offered more than the company could use. “At that time we could source most of what we required from Nelson Potter Ltd who did most of the harvesting and extraction work for FC in these parts,” said Sarah. “Being near to and equidistant between Rendlesham Forest and Tunstall Forest we could not have been in a better location.”

Timber supply tightens

All that has changed, with timber supplies increasingly difficult to obtain at an affordable price. “The basic background problem is a three-decade hiatus in commercial conifer planting starting around 1990 and continuing to this day. With no planting of any consequence for nearly 30 years we are now desperately missing those first thinnings,” she said.

“During the last 5 to 6 years FC has changed its standing timber sales policy and stopped all small sales to the disadvantage of small local forestry contractors on whom we relied for supplies and who clearly cannot cope with such volumes,” said Sarah Brown. “With supplies increasingly in the hands of a few large contractors invariably from outside, coupled with already high and still rising prices, there is a tendency for timber to be shipped out of East Anglia again. Difficulty in sourcing supplies is rapidly approaching crisis point,” says Sarah.

However, the more immediate constraint on Eastern Woodfuel, directly related to shrinking supplies and perhaps having a few large contractors controlling sales, is the escalating price of timber across all grades including bentwood traditionally chipped for biomass burning. “Bad for us because we cannot compete with other sectors possessing more favourable economics of operation and greater scope for raising the price of their finished product,” Sarah told Forestry Journal. In this she is talking about companies producing wood shavings for the equine bedding market and energy-hungry power stations consuming ‘anything and everything’ with a ‘ligno-cellulose’ content. “In this context ‘the more you burn the more you earn’ philosophy behind RHI has not necessarily done Eastern Woodfuel any favours,” says Sarah, explaining how processing of wood for biomass burning is not as simple as it first seems. One tonne of green timber takes 18–24 months to dry (depending on winter conditions) and loses a third of its mass along the way including a period of storage ‘in the round’ on a windy site prior to chipping. Pine presents another problem. “Pine can be dried down to a point where the wood becomes over-dry and therefore starts to absorb water because the capillaries have opened up,” says Sarah.

An uncertain future for biomass burning

Summing up, Sarah paints a potentially bleak picture for the future. “It’s becoming as hard as hell to obtain wood for chipping. We are now paying four times as much for supplies as when we started out 10 years ago and the profit gap between buying in raw wood material and delivering the finished woodchip product is virtually halved. Margins are already small and getting smaller. We see the price of timber rising relentlessly with the price of our finished product unable to keep up. Eastern Woodfuel is a winter-focussed business and the company is still going only because it is part of a much bigger and more diverse company. Eastern Woodfuel could not stand alone,” says Sarah.

On the train back to London I mulled over what I had heard that day. It beggars belied that the national and county authorities which established the system some ten years ago did not take into account potential problems created by steep and rapid declines in tree planting, already in progress for almost two decades; clearly preventing locally-focussed biomass burning being anything other than a trendy ‘flash in the pan’. By its very definition a sustainable renewable heat incentivised system requires fuel materials to be renewed.

Dr Terry Mabbett

BOXOUT

P R Newson Ltd

Wood chipping at Bentwaters Parks, underway while we were there, is carried out by P R Newson Ltd based at Buntingford in Hertfordshire. Established in 1987, P R Newson offers all wood fuel production related activities to wood fuel supply companies and owners of biomass boilers.

Company owner Philip Newson told Forestry Journal: “We run two dedicated biomass chippers, one towed and fed by crane lorry and the other self-contained with its own loading crane and based on tracks. In the future we are investing in small ‘all terrain’ chippers to focus on recovering smaller amounts of fibre that is currently unused in an attempt to tackle the problem of short supply.”

On reading the article Philip Newson said: “This pretty much sums up what we have been hearing from our other customers. I think it is a sad state of affairs when domestic users needing only 100t/year or so are struggling to find supplies. These are the users that should be supported the most.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here