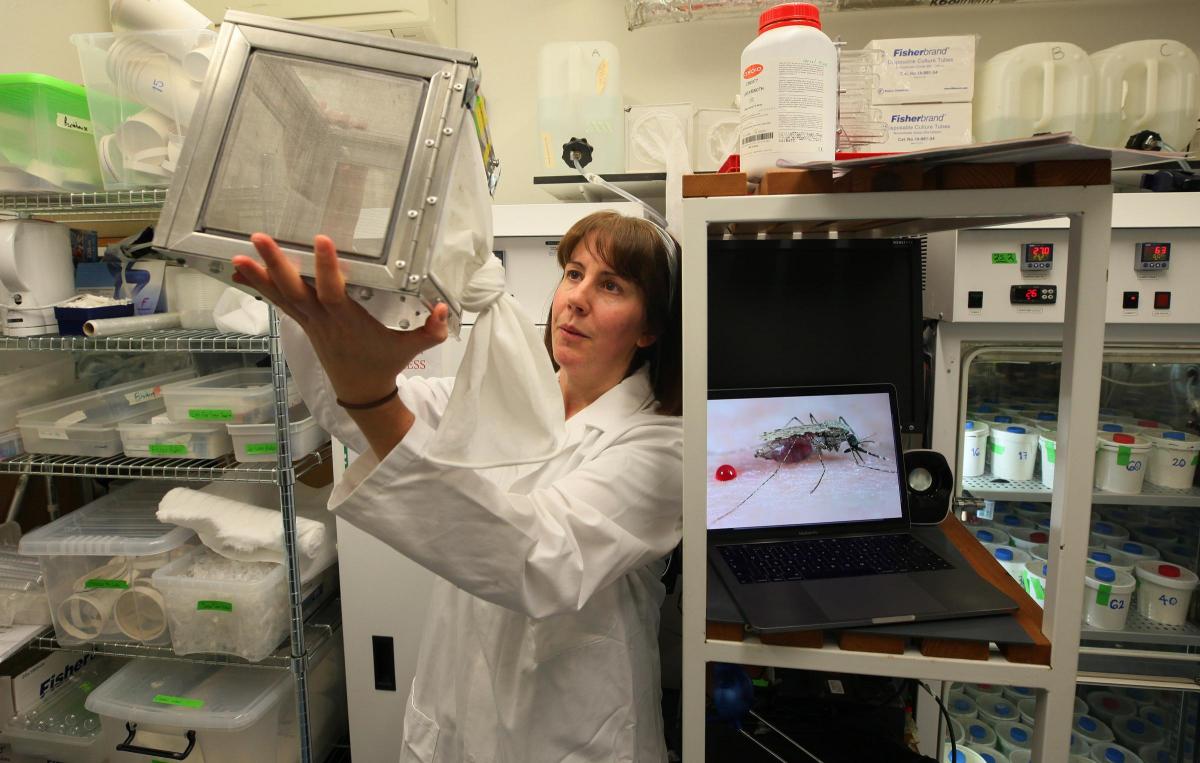

Professor Sarah Reece

WHAT makes a successful parasite? That's the question I'm trying to answer through my work as Professor of Evolutionary Parasitology at the University of Edinburgh. My research focuses on malaria parasites and uses evolutionary biology to understand the strategies that the parasites have evolved to survive and spread.

I head up a 10-strong team and one of the things we look at is the challenges that being a parasite brings. The host they are inside is constantly trying to get rid of them. That can be a brutal environment. We use knowledge of the strategies that animals, birds, plants and insects have evolved to ask how sophisticated parasites are.

Parasites have been rather underestimated. While they don't have brains or neurological processing powers, they do behave in similar ways to these other creatures. Our work involves assessing how parasites interact with each other and cope with the changing environments they experience inside hosts and the vectors, such as mosquitoes, that transmit them.

We know that parasites can work together to overcome their host and organise themselves according to the time of day. They have quite a lot of different tactics to help themselves when their hosts are treated with anti-malarial drugs. We are uncovering how good they are at moving the goalposts when medicine attacks them.

READ MORE: The magic of ship models – new catalogue charts the Glasgow Museums collection

Malaria parasites and their relatives are responsible for some of the most serious diseases of humans, livestock, companion animals and wildlife. For example, almost half the world's population are at risk from malaria; it kills approximately half a million people each year, mostly children under five, and several hundred million cases occur annually.

It is a complex disease and a sophisticated parasite. Over the past decade, there has been a very promising reduction in the number of malaria cases. However, progress in reducing malaria has slowed dramatically over the last 18 months to two years. It looked like everything was going well towards elimination but now eradication of the parasite is looking further away.

History tell us that parasites evolve. Malaria parasites are famous for their ability to resist anti-malarial drugs. We know that if we attack the parasites, they are going to move the goalposts. The questions are how far are they moving them, how quickly and where do they end up? We aim to couple this knowledge with information on how parasites make decisions to improve our armoury against parasites.

There is still an ambition to eliminate malaria by 2050 but that depends how the parasites respond to what we do to them. Eliminating malaria requires finding new ways to kill parasites that are more difficult for evolution to overcome than the drugs we currently have. Every time we do an experiment to ask a particular question, the insight we gain throws up at least 10 new questions.

READ MORE: The magic of ship models – new catalogue charts the Glasgow Museums collection

It is a bit like travelling up a tree. You start at the trunk and need to find your way through the branches and twigs towards the top. It is exciting getting results from experiments because you have learned something that no one knew before.

Parasites: Battle for Survival is at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh until April 19. Visit nms.ac.uk/parasites

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here